I’ve recently reintroduced direct moxibustion into my practice. I had left it for years while running a community acupuncture clinic; I couldn’t really get it to fit into the treatment model. Now that I am doing more private treatments, I have been getting back up to speed with it. For those who have never used the tiny direct moxa, it is incredibly useful addition to one’s clinical skillset. It is not hyperbole to say that I have seen some astounding results with it.

Back in the late 1990s through the 2000-aughts, I used to teach Japanese acupuncture and moxibustion skills that I had learned from various teachers around the U.S. and in Japan. I still have a lot of material that was included in the handouts for these seminars I would teach. Since my primary outlet of professional communication is through this here Substack, quite a bit of it is finding its way onto the mulch pile – many of the early posts are abstracted versions of the handouts I made for those classes. This post is yet another.

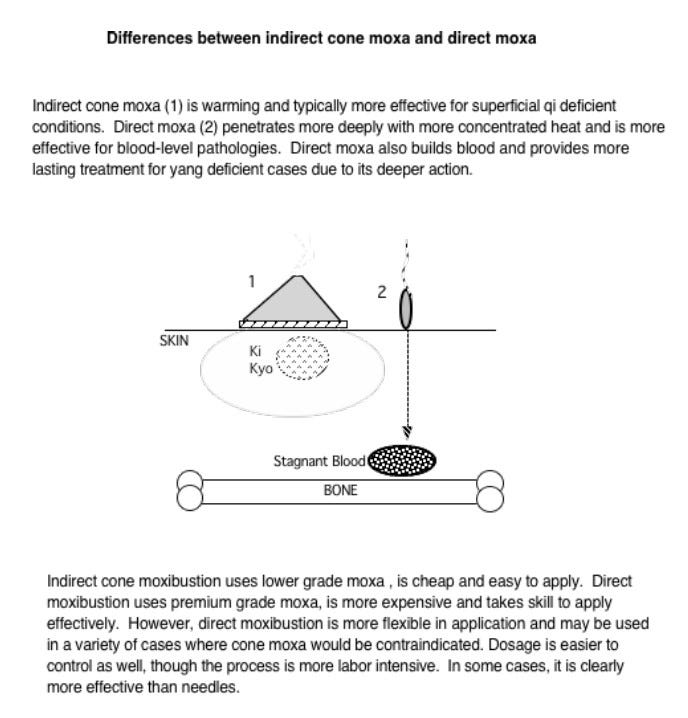

First up is a screenshotted image file. The copyright mark is from 1999. The graphics were made in Clarisworks, if I’m not mistaken. Ah, the old days…

Another page of the handout was tips for practicing and applying the moxibustion:

Points to consider in direct moxibustion

1) Use the best quality gold moxa. Cruder moxa is more difficult to roll and burns unevenly at a higher temperature, increasing the risk of inadvertantly burning the patient.

2) Do not roll the moxa too tightly. Tightly rolled moxa burns more slowly and much hotter. You may want to pre-roll the moxa with business cards or wood blocks before the treatment.

3) Use small cones of roughly equal size. Half-rice-grain size is the standard. Although this can be difficult at first, try to deliver as even a stimulus as possible.

4) Prepare the point. The points are always found with palpation. Once the point is located, prepare it with some shiunko ointment (lip balm will do if nothing else), or a moxa shield. This is both to protect the skin as well as help the moxa adhere vertically to the point. Some practitioners instead moisten the bottom of the cone with water or saliva (not recommended). This helps the cone adhere but does not do much to protect the skin from burns. Only attempt this once you know what youʼre doing.

5) Control the heat. If the patient is sensitive, it is best to use your fingers or a tube to press lightly around the point. This reduces the sensation as well as the rate of combustion. Make sure you donʼt burn your fingers. It is often advisable to pinch out the moxa as it burns to the skin, especially for the first cone placed. Succeeding cones can be then placed on the ashes of the previous ones, which further shields the skin.

6) Burn 3-7 cones for each point. This is the general rule. I usually burn until the skin gets red and then stop. More sensitive skin means less moxa. In more severe cases I may use 21 cones for each point, but this is the exception. More cones means there is more likelihood of an adverse reaction, so be careful.

7) Always be aware of both hands. Especially the one holding the incense. Remember, the incense is hotter than the moxa, and it will cause a more severe burn if it touches the skin.

As always, the key is practice practice practice. If you are totally in the dark about how to start, or you have some idea or maybe even some skills that you want to improve on, there are some excellent opportunities available online. I’ll mention two of them that I’m familiar with.

TJM Seminars of Portland is hosting a sort of online Moxa-palooza with three very experienced and gifted teachers, dedicated to presenting a variety of moxibustion techniques. The date is December 10-11, 2022, and you can find more information here.

Another well-known teacher I have benefited from is Alan Jansson, who has an online program at World Acupuncture. He is a longtime practitioner and personal student of Ikeda Masakazu sensei, one of the most influential figures in Traditional Japanese Medicine.

I have no financial or other stake in these organizations, I just think it is really important to pass these methods on to the next generation of practitioners, so I thought I’d give them a shout-out.

For me, the techniques I learned in my Japanese acupuncture studies have been the foundation of my almost-30-years in practice. Developing this skillset can, I believe, elevate your practice and give you a level of distinction that can help you succeed in your practice goals. If you are at all attracted to this way of treating, I encourage you to seek out further instruction.

Note: this newsletter is for information purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. Please seek the opinion of a health care professional for any specific medical issues you may have.