In this series of articles, we’ve gone through the correspondences between Four Levels and our Five-Phase model in the treatment of Lurking Pathogens (LP). But what of the other major Warm Disease model, the Three Burners?

Where the Four Levels gives us a surface-to-depth map of the body, Three Burners gives us an upper-to-lower schematic. There are occasions in which one is more useful than the other, or may further clarify and explain the gaps in the other.

Transmission between Three Burners

In terms of overlay of the two models, the Upper Burner reflects the Wèi level, the Middle Burner the Qì level, and the Lower Burner the Xuè level. While the normal progression of disease is Upper to Middle to Lower, the overlay of the two models presents some alternative routes of pathogenicity. The Lung and Pericardium share a Burner, and their coexistence opens up the possibility of what’s known as abnormal transmission (nì chuán) of warm disease, in which the pathogen attacking the Upper Burner can make the jump from Wèi Level to Yíng level, skipping the Qì level altogether. Likewise, transmission in the Lower Burner may occur from the Large Intestine (generally thought of as a Qì level organ) to the Liver and/or Kidney (Xuè level), by virtue of occupying the same burning space.

Three Burners and damp warmth pathogens

Three Burners is also the most important means of differentiating damp and damp-heat diseases, especially. Since damp pathogens have a particular affinity for the Spleen, their place in Four Levels tends to be confined to the Qì level. While there are Wèi level damp pathogens, the Spleen is almost always involved, and the pathogenic factors generally penetrate to the Qì level and Middle Burner very quickly after onset. In this case, the general treatment strategy for the Lower Burner in particular changes from nourishing Yīn (more indicative of warm heat pathogen) to percolating dampness. The representative formula for this approach is Wú Jūtōng’s Three-Seed Decoction or Sān Rén Tāng from Wēn Bìng Tiáo Biàn (Systematic Differentiation of Warm Pathogen Diseases, 1798), which uses as its chief ingredients three seeds, one aimed at each Burner: xìng rén (Armeniacae Semen) for the Upper, bái kòu rén / bái dòu kòu (Amomi Fructus rotundus) for the Middle, and yì yĭ rén (Coicis Semen) for the lower. In the following case, we applied this formula idea to the root treatment with acupuncture.

Treating a Case of Crohn’s Disease with Three Burners Theory

A patient presented with a chief complaint of sinusitis with polyps, and a background of Crohn’s disease (CD). The patient noted a recurring process by which the sinuses would become infected, which would progress to bronchitis, and subsequently lead to a flare of the CD symptoms (typically dull abdominal pain and evacuation of bloody stool). Other complaints included stuffy chest, acid reflux and fatigue. The abdomen was slightly bloated and there were some red pimples on his chest and upper back. The tongue body had red sides and a somewhat thick dry coat. The pulse was rapid and slippery.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis was damp-heat in the Three Burners at the Qì level. This could have been seen as a standard TCM damp-heat case, but the patient offered an assessment of his own pathogenesis which was striking in its resemblance to Wú Jūtōng’s Three Burners theory. Though chronologically the patient’s CD developed long before his sinusitis, the current trajectory of flare-ups closely followed Wú Jūtōng’s description of pathogens descending from the nose into the chest (Upper Burner), from the chest into the stomach (Middle Burner), and into the Intestines (Lower Burner).

Analysis

The obstructive sinusitis with polyps, dull aching abdominal pain, rapid slippery pulse, and thick tongue coat indicated the presence of heat and dampness. The dryness of the tongue coat, the thick nasal mucus and pimples suggested the steaming of fluids in the Upper Burner due to disruption of the Qì dynamic in the Middle Burner. With the Spleen unable to ascend clear Qì and fluid and the Stomach unable to descend, turbid damp would accumulate in the Stomach and Intestines, creating depressive heat that would eventually transfer in the Lower Burner to the Xuè level, scorching the vessels and causing a downpour of turbid damp and extravasated blood.

Treatment principles

As the patient showed no significant signs of vital substance deficiency, treatment was focused on enabling the body to eliminate pathogenic factors, primarily by opening the orifices and venting the Lungs, rectifying the Qì dynamic particularly of the Spleen, and clearing the Sān Jiāo. This reflects some key ideas in the Warm Disease school. Wú Jūtōng noted that as the Lungs govern the Qì, they are key to transforming dampness. Yè Tiānshì wrote that “Upper [Burner] failure to clear and regulate” damp heat would result in transmission to the Middle and Lower Burners. Zhāng Xūgǔ observed that the Spleen is linchpin of the ascending and descending movement of Qì in the Sān Jiāo, and rectification of the Spleen’s Qì dynamic will ensure proper functioning of the Upper and Lower Burners (Clavey, 2003, p 421-423).

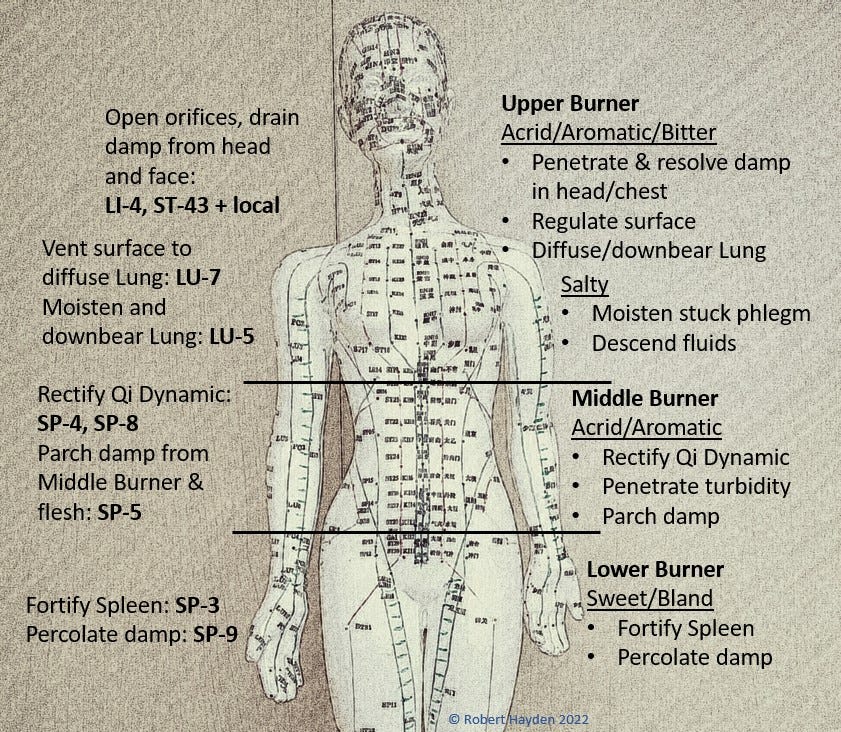

Figure 1 shows a schematic of the treatment points and principles. The pattern is a Lung shō at the Qì level, but in contrast to the previous post on this pattern the pathogen is damp-heat rather than wind-heat, which makes it imperative to regulate all three Burners at once – similar to the Sān Rén Tāng strategy.

Figure 1

The points in Figure 1 were the main points primarily for root treatment of the shō; points at each session were selected from the list. Typically two points from the Lung and two from the Spleen were treated each time. Lung points were more constant where Spleen points were selected according to whatever the patient presented with at that particular session. If there was more dampness, perhaps SP-9 (yīn líng qúan) and SP-5 (shāng qiū) would be selected. If the Qì Dynamic was depressed, giving more pain, reflux, and stagnation symptoms, SP-4 (gōng sūn) and SP-8 (dì jī) were more likely used.

Additionally, Ren-6 (qì hǎi), Ren-12 (zhōng wǎn) and Ren-17 (shān zhōng) were usually needled to target each of the Burners. Local points for the sinuses were treated, and back points such as GB-20 (fēng chí), BL-13 (fèi shū), and BL-20 (pí shū) were used. There were some interesting twists in this case involving pathogens switching from Yáng Míng to Shào Yáng stages, which necessitated some changes in Yáng channel point selection, but the basic treatment principles of treating Lung, Spleen, and Sān Jiāo were constant throughout.

In the next installment, we’ll wrap things up with some discussion about the Yíng level (and ghost diseases) with some case examples.

Note: this newsletter is for information purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. Please seek the opinion of a health care professional for any specific medical issues you may have.

References

Clavey, S. (2003). Fluid physiology and pathology in traditional Chinese medicine (2nd ed). Churchill Livingstone.

Ellis, A., Wiseman, N., Boss, K., & Cleaver, J. (2004). Fundamentals of Chinese acupuncture (Revised ed). Paradigm Publications.

Hayden, R. (2021). Five phases, four levels, three burners: Building resistance in the pandemic era. North American Journal of Oriental Medicine. 27(83). 5-6.

Liu, G. (2005). Warm pathogen diseases: A clinical guide. Eastland Press.

Scheid, V., Bensky, D., Ellis, A., & Barolet, R. (2009). Chinese Herbal Medicine: Formulas & Strategies (2nd ed.). Eastland Press.