As mentioned earlier, the concept of Lurking Pathogens (LP) dates back to the origins of canonical Chinese medicine. In Huáng Dì Nèi Jīng Líng Shū 58 there is a passage which refers to LP in all but name. It implies several etiologies: dampness and trauma, triggered by emotional upset, dietary and/or seasonal factors. There are even instances resembling ghost diseases.

From The Systematic Classic of Acupuncture (Zhēn Jiǔ Jiǎ Yǐ Jīng), translated by Yang & Chace, pp 346-347 (original source Líng Shū 58):

The Yellow Emperor asked:

If bandit wind and evil Qì damage people, these factors will cause them to contract disease. Now, there are persons living well within the protection of screens and curtains who never step out of their chambers or cave dwellings, and yet they may suddenly become ill. What is the cause of this?

Qì Bo answered:

All of these have, at some time, been damaged by damp Qì which hides inside the blood vessels and in the parting of the flesh. (This evil) has been retained for a long time without departing. (These people may have had accidents) such as falls, and the resulting foul blood has become lodged internally and not eliminated. When one experiences sudden, inordinate joy or anger, or undisciplined diet, or unseasonal temperature changes when the interstices are shut and blocked or wind cold strikes the opened (interstices, all these factors cause) blood and Qì to become congealed and bound. (The new and old) evil conspire together and launch an attack. […] Even though they have not been caught by a bandit wind and evil Qì, (the trouble) must be initiated by an additive factor.

The Yellow Emperor asked:

All that your honor has explained is apparent to the patient himself. Suppose one has never been caught in an evil wind and is free of such emotions as apprehension and fright but suddenly falls ill. Then what is the cause? Should it be ascribed to the work of a ghost or god?

Qì Bo answered:

In this case also, there must be an old evil which has never before been apparent. When the orientation is affected by antipathy or compassion, Qì and blood become internally chaotic. Then these two Qì join forces to cause oppression. The (evil) that comes (from the past) is fine, invisible to the eye, and inaudible to the ear. Therefore, it seems like a ghost or god.

In Four Levels, both the congealing and binding of blood and the appearance of ghost-disease-like symptoms are the province of the Yíng level. In our scheme, this is the Pericardium shō, also involving the mother organ Liver. As the two are hand and foot Jué Yīn, signs of reversal are also evidence of LP at the Yíng level. As the heat and dampness dessicate and/or congeal the blood, interior wind symptoms such as tics, tremors, and spasms become prominent.

Treatment of Yíng level pathology, a case study

A patient presented with complaints of physical and vocal tics, depression, lack of energy, aural and visual hallucinations, clouding and confusion, and self-harm. Signs included cold hands and feet with warm arms and legs, and a rapid, thin, wiry pulse. The tongue was dark red on the sides and tip, with a dusky center. The tip had an unusual feature of a darker semicircle behind Heart area. There was no coating on the tongue.

Assessment

The Chinese medicine diagnosis was Yíng-level Heat in the Pericardium and Liver. Maciocia (2022, p. 517) lists mental confusion, incoherent speech, delirium, body hot with cold hands and feet, a red dry tongue without coating, and a fine-rapid pulse as clinical manifestations of Pericardium Nutritive (Yíng) level Heat. The wiry pulse and the tics indicated the involvement of the Liver, specifically the stirring of wind from the heat and damage to Yīn-fluids. The altered psychological state of the patient went beyond mere irritability and agitation. There were no tongue sores such as might appear in Heart Fire; the dark red crescent appearing behind the tongue tip was interpreted as indicating intensive heat in the Pericardium. There were no complaints of hypochondriac pain or headaches to suggest Liver Qì constraint with heat. The possibility existed that the clouding could be due to phlegm, though there were no outward manifestations to determine its presence. With no indication of a precipitating exogenous heat pattern, the question of whether the presenting case represented a Lurking Pathogen was considered.

Treatment

The treatment plan goals were to reduce the frequency of the tics, help lift the depression and ease the psychological symptoms. The Chinese medicine treatment principles were to clear heat from the Pericardium, vent Yíng level heat outward to the Qì level, settle the Liver and extinguish wind, and calm the spirit.

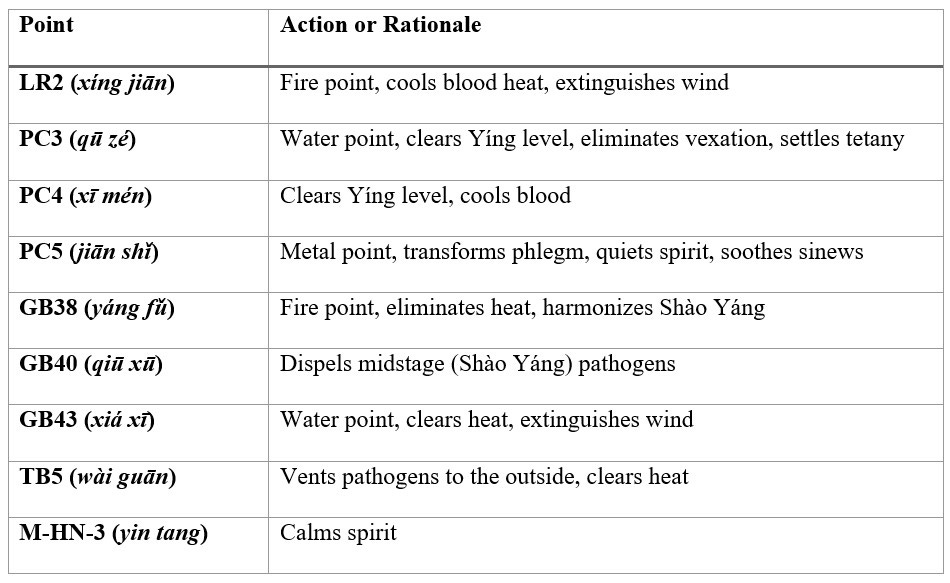

Table 1 shows the points selected:

Point selection was based mainly on patient presentation at the time of the session. Typically two upper limb points and two or three lower limb points were chosen, along with M-HN-3 (yìn táng) .

The tics had significantly reduced after three treatments, and the hallucinations had become less frequent by the seventh session. The patient’s hands and feet had become warm and sweaty, and the coating on the tongue returned and thickened before normalizing. The pulse went from wiry to slippery to choppy as the treatments continued. In general, though the course was not completely linear, the regression of the pathogenic factor from Yíng to Qì level was observable by the patient’s signs over the treatment course. By the twelfth session the patient discontinued treatment.

At six months’ follow-up the patient had been free of the presenting symptoms since the end of the treatment course.

Discussion

Was this a Lurking Pathogen (LP) case? My assessment is that it was, triggered by stressful events in the patient’s life. Disturbed Jīng-Shén, clouding confusion, and hallucinations were followed by interior wind (tics), showing a progression of disease from Yíng level (Pericardium) to Xuè level (Liver). One of the characteristics of a LP is that as the disease improves the signs and symptoms will reflect the pathogen being outthrust to a more superficial level (Liu, 2005, p. 84). In this case, the initial onset reflected Yíng/Xuè level, including the uncoated red tongue and fine rapid pulse; the subsequent course of therapy saw the appearance of Qì level signs (return of tongue coating, temporary loss of appetite and smell, slippery pulse) which suggested the pathogen was being pushed toward the surface and Yáng organs where it could be resolved.

To put it another way: if this wasn’t a LP, it surely behaved like one on the way out.

As indicated by the Líng Shū 58 quote above, LP need not be restricted to the course of exterior diseases. Even among Warm Disease theorists, etiologies and triggering factors varied. The crucial elements are

the determination of the location (in terms of Four Levels, Three Burners, membrane source, etc) and nature (heat, summerheat, damp, dryness, etc) of the pathogen, and

the process by which it is dredged up and vented toward the more superficial layers of the body and their various routes of elimination.

Note: this newsletter is for information purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. Please seek the opinion of a health care professional for any specific medical issues you may have.

References

Ellis, A., Wiseman, N., Boss, K., & Cleaver, J. (2004). Fundamentals of Chinese acupuncture (Revised ed). Paradigm Publications.

Liu, G. (2005). Warm pathogen diseases: A clinical guide (Revised ed). Eastland Press.

Maciocia, G. (2015). The foundations of Chinese medicine: A comprehensive text. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Mi, H.-F. (2004). The systematic classic of acupuncture (S.Z. Yang & C. Chace, Trans.). Blue Poppy Press. (Original work published n.d.)