In describing our process of integrating acupuncture treatment into the Warm Diseases model, we wanted to include some discussion of needle techniques. In Japanese Meridian Therapy (JMT), the emphasis is on tonification of the Zàng organs by the mother-child method in Nán Jīng 69, and the most common needling methods to achieve this (slow insertion, quick withdrawal, insertion in exhaling and withdrawal on inhaling, closing the needle hole) come from Huáng Dì Nèi Jīng Líng Shū. But Nán Jīng 69 also uses the mother-child rule to drain excess, and in dredging and venting Lurking Pathogens (LP), we are dealing with the concept of draining. We could, of course, use the methods from Líng Shū for draining, but there is an intriguing alternative in Nán Jīng.

Nán Jīng 76 and 78: Yíng-Wèi needling

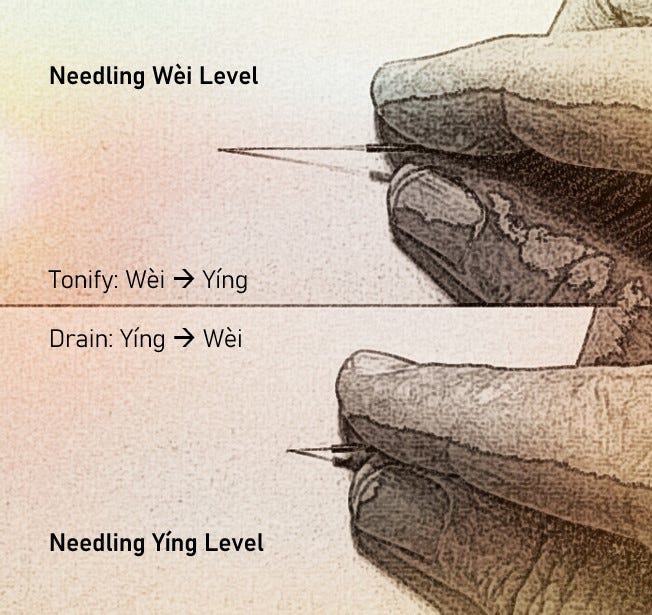

Nán Jīng 76 and 78 discuss supplementing and draining techniques, using a bi-level scheme of needling in which qì is gathered at one level and the needle is then advanced or withdrawn to a second level. In tonification, the qì is gathered at the superficial level and the needle is advanced to the deep level. In draining, the needle is initially inserted more deeply, then the qì is gathered and the needle is withdrawn to the superficial level. In chapter 76, the deeper level is identified with the Yíng and the superficial is identified with the Wèi, which gives the image of encouraging qi to move from the Yíng level to the Wèi level in cases of excess or pathogenic qì, and thus echoes the Warm Disease core principle of venting the pathogen.

Needle and moxa techniques

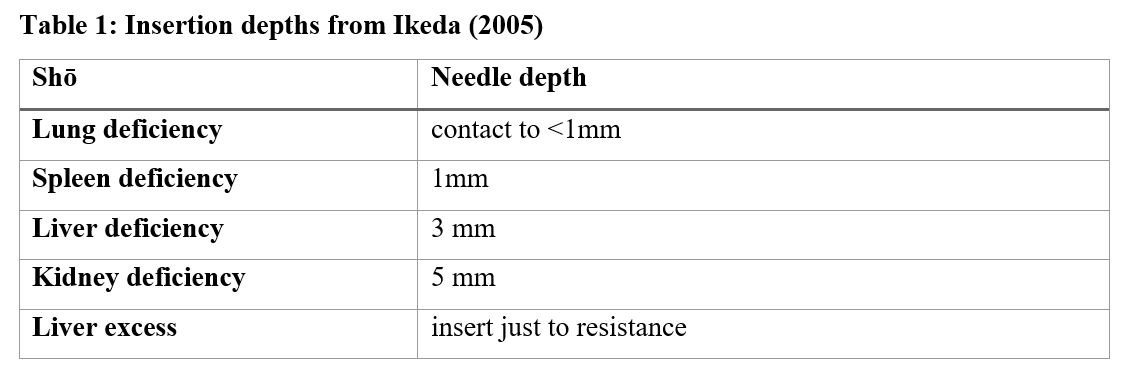

JMT is notable for its delicate approach to needle technique. The depths of insertion, particularly for the treatment of the root, i.e. the four basic shō, are quite superficial. In addition, non-inserted or contact needling (sesshokushin), in which the tip of the needle is brought to the skin but does not penetrate, is frequently used (Shudo 2003).

Ikeda (2005) gives the following guidelines for the depths of insertion in root treatment (Table 1):

In venting the pathogenic factor, we have been using a similar idea of depth to the one in the table above, i.e., inserting to the depth where resistance becomes apparent. This depth, naturally, varies with the anatomy of the point and the build of the patient. In a point in deeper tissue such as SP-8 (dì jī), this is often about 10-15mm. More superficial points are of course needled more superficially. Typically we use a 0.12 or 0.14x30mm needle. Once the resistance is felt, we often use a plucking or flicking technique at the needle handle to induce a vibration into the point with the intention of dislodging the pathogen. Then the needle is withdrawn to a more shallow depth to encourage venting, then often retained for 15-20 minutes (or possibly removed if the patient is very sensitive and/or the point is found to be nearer to the surface).

Needling to release the exterior

A technique that is frequently used in JMT is called scatter needling (sanshin) (Ikeda 2005). Scatter needling is quick contact or superficial needling done over an area of the body rather than a specific point. For supplementing, the “holes” made by the needle are closed as the needle is withdrawn, while for draining, the “holes” are left open. The draining sanshin frequently has the effect of opening the surface and venting heat.

Venting heat with moxibustion

Another technique appropriate for venting pathogens is known as chinetsukyū, or heat sensation moxibustion. In chinetsukyū, a small cone of semi-pure moxa is placed on the skin and burned until the patient indicates that a heat sensation is felt. At that moment, the burning moxa is removed. The purpose of chinetsukyū is to open the surface to vent heat, usually in cases where there is superficial heat and fluid congestion, such as a sprain (Hayden, 1999; The Society of Traditional Japanese Medicine, 2003).

Conclusion

This is of course far from the final word on technique for venting LP with acupuncture and moxibustion, but it does represent some applications we have found useful in the clinic. As this is a work in progress, more refined techniques are likely to develop. As the JMT masters never tired of telling us, “practice, practice, practice” is always the requirement for best results.

Note: this newsletter is for information purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. Please seek the opinion of a health care professional for any specific medical issues you may have.

References

Hayden, R. (1999). Thoughts on Using Chinetsukyu in Meridian Therapy. North American Journal of Oriental Medicine (NAJOM), 6(17), 18-19.

Ikeda, M. (2005). The practice of Japanese acupuncture and moxibustion: Classical principles in action (E. Obaidey, Trans.). Eastland Press. (Original work published 1996).

Shudo, D. (1990). Japanese classical acupuncture: Introduction to meridian therapy (S. Brown, Trans.). Eastland Press. (Original work published 1983).

Shudo, D. (2003). Finding effective acupuncture points (S. Brown, Trans.). Eastland Press.

The Society of Traditional Japanese Medicine. (2003). Traditional Japanese acupuncture: Fundamentals of meridian therapy (J. Margulies, Trans.). Complementary Medicine Press.

Unschuld, P. U. (1986). Nan-ching: The classic of difficult issues: with commentaries by Chinese and Japanese authors from the third through the twentieth century. Berkeley: University of California Press.