First, some upcoming stuff…

I’m getting ready to launch two different online CEU courses. One is on treating headache and primarily focuses on acupuncture; it is being done in collaboration with TCM Academy of Integrative Medicine and is set to kick off with a live session on December 16th. The other is a course on treating pain with Chinese herbal medicine, and will be offered through East-West College of Natural Medicine in Sarasota, Florida, USA. For that one, I am just finishing the recordings this weekend. I’ll update when the course is posted.

In the meantime, I wanted to put up a quick mulch post. I promised something on acupuncture, so here’s a little morsel.

Treating Cough

It’s well into metal season, and I am seeing a fair amount of cough in the clinic. Usually people don’t come in for help with coughs until they become chronic, unless they are accustomed to getting acupuncture to help them get over seasonal pathogens. So I suspect that once metal season has passed, there will be more folks who had exterior contraction cough in the autumn and were unable to shake it by winter.

My approach to treating cough is usually pretty straightforward. I generally start with the lung, i.e., treating the lung pattern. Often times there is a lingering upper respiratory issue, commonly sinusitis, which may contribute to the chronicity of the problem. Pathogens lodged in the sinus can make their way to the lungs and further block the qì dynamic of the upper burner, provoking cough. A recent case of a patient with a months-long cough, chronic sinus congestion, and digestive disruption responded quite well to the following treatment:

LU5, LU7, SP9, SP5 (5-phase lung pattern)

CV6, CV12, CV17 (regulate three burners)

LU1 (lung mù point)

LI4, ST43, ST36 (yángmíng channel)

Yìn Táng, ST3 (local sinus treatment)

UB12, UB13, UB17, UB20, UB43

The root treatment of the lung pattern here consists of LU5 to downbear lung qì and eliminate phlegm, LU7 to vent pathogens to the exterior, SP9 to transform phlegm-dampness, and SP5, the metal point, to dispel dampness and relieve coughing.

The three burners combination is one I use to open the flow between the upper, middle and lower. The lung mù point is used to treat the cough. LI4 and ST43 is a combination I use frequently, that I learned as an extended extraordinary vessels pair with Fukushima Kodo’s group; I use it to open the nose, among other things. ST36 is used to help regulate the middle and downbear the qì. The sinus points are, well, sinus points. The back points are to eliminate wind (UB12), supplement lung and spleen (UB13, UB20), and open the diaphragm and upper back (UB17, UB43).

A Perspective from the Qīng Era

I was scrolling through some acupuncture texts a few days back, looking for something easy to translate, and I happened upon this passage from Zhēn Jiǔ Féng Yuán (針灸逢源, Encountering the Origins of Acumoxa) by Lǐ Xuéchuān, written in 1815 during the Qīng era.

咳嗽哮喘門

咳嗽 有聲無痰曰咳傷於肺氣也。有痰無聲曰嗽。動於脾濕也。有聲有痰。名曰咳嗽因傷肺氣。復動脾濕也。

天突 膻中 乳根(三壯) 風門 肺俞 經渠 列缺 魚際 前谷 三里

Cough, Wheezing and Panting Gate

Cough (Ké Sòu)

If there is sound but no phlegm is called “ké”, [caused by] injury to lung qì. If there is phlegm but no sound it is called “sòu”, [caused by] stirring of spleen dampness. If there is sound, and there is phlegm, it is named “ké sòu” as its cause is from injury to lung qì and its recurrence is from stirring of spleen dampness.

Tiān Tū [CV22], Shān Zhōng [CV17], Rǔ Gēn [ST18] (3 cones of moxa), Fēng Mén [UB12], Fèi Shù [UB13], Jīng Qú [LU8], Liè Quē [LU7], Yú Jì [LU10], Qián Gǔ [SI2], Sān Lǐ [ST36].

This is not too far off from my treatment above, minus the points to address the sinuses and middle burner issues. The general approach works well, for the most part, until of course it doesn’t. More severe coughs may not respond as well. At that point, what do you do?

Lǐ Xuéchuān continues:

咳逆 因喘咳以至氣逆。咳嗽之甚者也。

肺俞 肺募 太陵 三里 行間

Cough and Counterflow [ké nì 咳逆]

Caused by panting and coughing to the extent that the qì counterflows. It is a severe case of cough.

Fèi Shù [UB13], Fèi Mù [LU1], Tài Líng [PC7], Sān Lǐ [ST36], Xíng Jiān [LR2]

Wiseman’s Practical Dictionary (1998) describes the pathocondition ké nì 咳逆 as follows:

Counterflow Qì Ascent Cough咳逆上气 ké nì shàng qì

Cough and counterflow qì giving rise to panting. Counterflow qì ascent cough stemming from contraction of one or more of the six excesses or from phlegm-rheum collecting internally forms a repletion pattern. Occurring in enduring illness or as a result of major damage to original qì, it takes the form of a vacuity pattern. In all cases, it is associated with disease of the lung, spleen, and kidney, since it can result from congestion or vacuity of lung qì, from impaired splenic movement and transformation, and from the kidney failing to absorb qì. Persistent counterflow qì ascent cough can gradually give rise to debilitation of heart qì.

Often, when respiratory syndromes become severe, it is a kind of given that the focus of pathology move from lung and spleen to the kidney – after all, we were drilled with the lung-vs-kidney-type wheezing (labored exhalation vs labored inhalation), one being more pathogenic excess and the other being more indicative of yang deficiency.

But Lǐ is not really talking about that here. There are no kidney points, though there are two points that pertain to the lungs. Instead, we are presented with pericardium and liver channel points. What I see are a couple of possible mechanisms to this point selection.

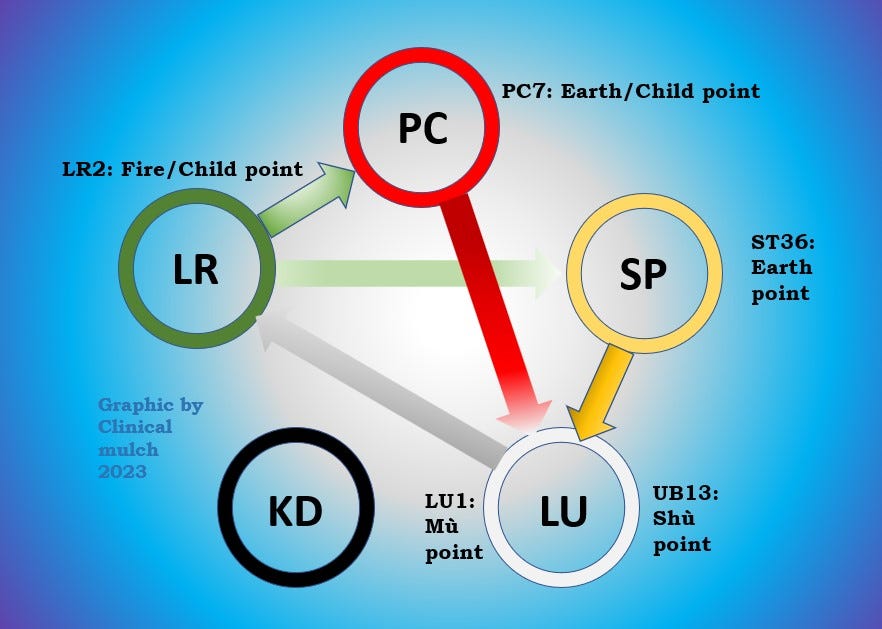

Engendering and Controlling

First, and most obvious to my five-phase-attuned brain, is that the two channels are in a mother-child relationship; they form a pericardium pattern, or, looking at it another way, a liver excess pattern. Both pericardium and liver stand in a control-cycle relationship to the lung, and the liver has a controlling relationship to the spleen. LR2 is the child point in the mother-child relationship, which according to Nán Jīng (Classic of Difficulties) chapter 69, should be drained in cases of repletion. PC7 is also the child point, but in more orthodox five-phase point selection the point to treat to drain the liver would be PC8. However, a section on mother-child theory in the Zhēn Jiǔ Féng Yuán makes no mention of specific points to treat. LU1 may be used to eliminate pathogenic factors from the lung and UB13 used to supplement the lung qì, with ST36, the earth point, doing its earth thing by supplementing the center and downbearing the qì.

In a diagram, it might look something like this:

In other words, the pathomechanism behind the point selection could be wood insulting metal, liver repletion with lung vacuity. I’m inclined toward this interpretation in part because, in looking through lists of actions and indications for PC7, I can find almost nothing that would suggest it as a key point in severe respiratory syndromes. The same goes for LR2. The five-phase dynamics here, as I said, seem quite obvious.

Rectifying Counterflow

The second possibility I see is a strategy of rectifying counterflow by treating juéyīn. The pericardium and liver are hand and foot juéyīn channels, respectively. The pathology here is that the cough is so severe that it completely upends the qì dynamic, similar to a state of reversal (jué). A confirming sign of this would be cold hands and feet.

This view is taking a step back and looking at the situation from the perspective of channel theory and global qì flow, rather than focusing on interrelationships of the zàngfǔ. Each of these ideas gives a different angle on the situation, and can be useful to consider even if the outcome (here in the form of point selection) is the same.

Anyway, that’s all I’ve got for now. Thanks for reading.

Note: this newsletter is for information purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. Please seek the opinion of a health care professional for any specific medical issues you may have.

References

Lǐ, X. (1815). Zhēn jiǔ féng yuán. https://jicheng.tw/tcm/book/%E9%87%9D%E7%81%B8%E9%80%A2%E6%BA%90/index.html

Wiseman, N. (1998). A practical dictionary of Chinese medicine. Paradigm Publications.