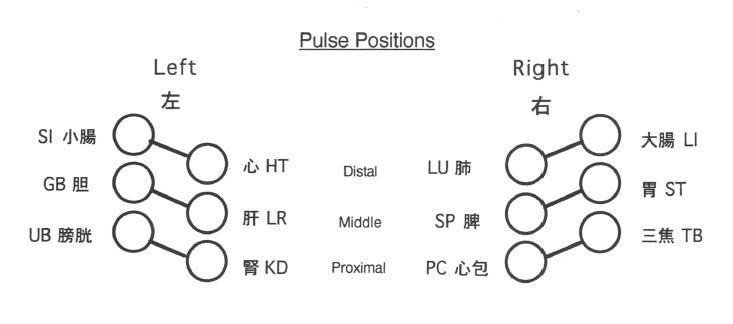

In most TCM patterns in the modern literature, pulses are described by their overall quality (wiry, soggy, slippery, choppy, etc.). In Japanese Meridian Therapy (JMT), once the basic overall quality of the pulse has been determined, the next step is to examine the pulse underneath each of your fingers. This is known as six position pulse diagnosis. This examination is important to help determine the sho, or pattern of disharmony, which serves as the diagnosis and is the basis of treatment in JMT.

(Please pardon my primitive graphics, made about 20 years ago on ClarisWorks, if you can believe that)

Six position pulse diagnosis comes from chapter 18 of Nan Jing (Classic of Difficulties). One of the many revolutionary assertions of the Nan Jing is found in the first chapter, which states that pulse examination — which in the Huang Di Nei Jing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic) took various forms such as palpating pulses at the neck or over the head, neck and extremities — could be conducted solely and completely at the radial artery of the wrist.

Yin meridians are found on deep level and yang meridians on superficial level. The way to find these is to first determine the middle depth of the pulse, and then determine the yin and yang depth levels.

First adjust all three fingers on each hand to find the depth where the pulse is felt most clearly beneath each finger; this is the middle depth.

Then, SINK the fingers toward the bone to find the YIN level, and FLOAT the fingers towards the surface to find the YANG level

In the diagram above, the different pulse positions are shown in yin-yang pairs, with the inside orb of the pair indicating the yin level and the outside orb indicating the yang level.

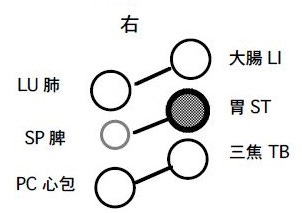

According to the principles of yin-yang, a pulse cannot be deficient in both yin and yang levels; if the yin level is deficient, then the yang level must be relatively excess, as illustrated in this diagram:

Here, the Spleen pulse is deficient and the Stomach pulse is excess, where the other pulses on the wrist are balanced on yin and yang levels. Sometimes, when you examine the pulse, one position may feel strong in both levels; this may be an indication of a yin-yang imbalance, and the yin level may actually be deficient. Some authorities on JMT say that one way to determine the most deficient yin meridian is to look for the largest yin-yang imbalance (Shudo, 1990). That can show up as a very full yang level pulse in one position, which can hide the deficient yin pulse. It is always good to check the pulse according to the generating and control cycles, as will be explained in next week’s post, just to make certain.

References

Shudo, D. (1990). Japanese Classical Acupuncture: Introduction to Meridian Therapy (S. Brown, Trans.). Eastland Press. (Original work published 1983).

Note: this post is for information purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. Please seek the opinion of a health care professional for any specific medical issues you may have.