Tài Yǐ and Thunder Fire

On the origins and uses of the humble moxa stick

About a year ago, I saw a post on social media from the The Academy of Source-Based Medicine which presented some brief translations of cases by modern Chinese masters. While these types of discussions can always be edifying, the fact that the cases presented were treated with moxa sticks (or poles, or rolls) was something I found fascinating.

I learned to use stick moxa in school, but never used it much over the years. I heard some very respected practitioners sort of dismiss it as not having much effect beyond keeping the customers happy. Over the past year since I saw the above-mentioned post, I have started looking at research specifically on moxa stick moxibustion. I plan to do a few articles on various aspects of the research. For now, let’s start with an overview of the practice with reference to the literature reviewed.

Some nomenclature

Some of the terms used in the literature for stick moxibustion include

艾條灸 ài tiáo jiǔ - poling; stick moxibustion

艾條灸療法 ài tiáo jiǔ liáo fǎ - moxa-pole therapy

悬起灸 xuán qǐ jiǔ –suspended (aka hanging) moxibustion

Other terms will be introduced as we go along.

Prevalence

Among moxibustion methods, suspended moxibustion with moxa sticks is the most frequently used method today, at about 31% (Huang et al, 2015) of the total treatments surveyed. But it was not always so. In fact, stick moxa as we know it is a rather recent addition to our treatment armamentarium.

Precursors to moxa sticks

In the classical period the moxibustion employed was primarily direct scarring moxibustion. As time went on, more and more ways to reduce the pain and tissue damage of this type of practice, such as introducing a barrier between the moxa cones and skin, were developed. However, one of the earliest examples we have of treatment via a burning substance suspended over the skin was not identified as moxibustion, but fumigation, in which the smoke was considered the therapeutic medium rathern than thermal stimulation. This was mentioned in Qiānjīn Yàofāng by Sūn Sīmiǎo [652] as well as Wàitái Mìyào Fāng by Wáng Tāo [752]. (Huang et al., 2015)

Another direct antecedent to suspended stick moxibustion was pressing moxibustion [實按灸 shí àn jiǔ] in which a lit roll of moxa (often along with other appropriate herbs) or another combustible rodlike material, such as a peach tree branch, was pressed into the point, which was covered by a barrier of several layers of cloth or parchment. This became popular in the Míng period through the Qīng and appeared in books by luminaries such as Zhāng Jingyuè and Yáng Jìzhōu (Wilcox, 2005; Huang et al., 2015).

There were various names attributed to the practice of pressing moxa, each indicating a specific prescription of moxa plus other substances which were rolled together. Some of these names are Taiyi Divine Needles (太乙神針 tàiyǐ shénzhēn), Thunder Fire Needle (雷火針 léihuǒ zhēn), and so forth. Various examples of these moxa rolls can still be obtained through acupuncture suppliers today.

Huang et al. (2015) place the transition of pressing to suspended moxibustion in the Qīng era. Chén Xiūyuán’s book Taiyi Divine Needle [太乙神針 Tàiyǐ Shénzhēn], written during that period, mentions a method by Yè Tiānshì in which the moxa stick was held about one inch over the skin (which was still covered by cloth) in order to heat the point slowly through the barrier.

Methods of suspended moxibustion were apparently around but not taken very seriously by doctors in the early modern era. In the Republican period, Chéng Dànān wrote that the method didn’t have much effect beyond increasing blood flow and reducing pain (Huang et al. 2015). In the years following, however, the practice became increasingly visible in the literature.

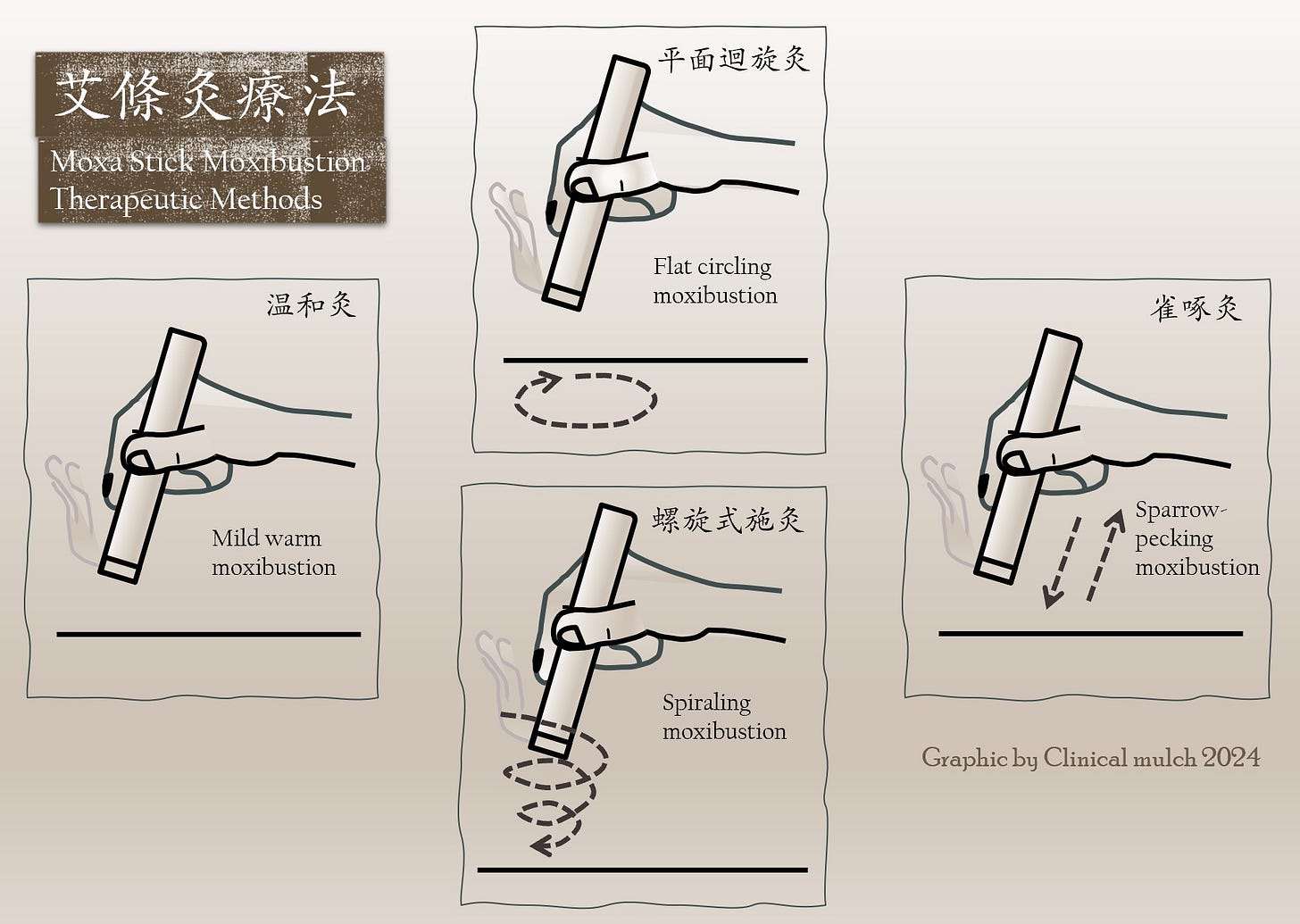

Three therapeutic methods

The literature we reviewed generally cites three main methods for suspended moxibustion (Huang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016: Zhao et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2020). These methods are:

Mild (mild warm, or gentle) stick moxibustion, 艾条温和灸 ài tiáo wēn he jiǔ

Circling (or circular, or rotating) moxibustion, 迴旋灸 huíxuán jiǔ

Sparrow pecking moxa stick moxibustion, 艾条雀啄灸 ài tiáo què zhuó jiǔ

We will examine each of these in turn.

1 Mild warm moxibustion

This is the most common of the three techniques

After lighting one end, hold the burning end 2-3 cm (1 inch) over the treatment point

The patient should feel a comfortable heat but not burning

Duration is generally 10-15 minutes each point, until the skin is red and slightly moist. The time can vary, however, which we will return to later.

Indicated for generalized vacuity, chronic diseases, cold-damp, nourishing life and disease prevention

Functions to supplement vacuity, warm yáng, harmonize zangfu

Yin et al. (2020) references a study using biorhythmic midnight-noon cycle to enhance the treatment effect

2 Circling moxibustion

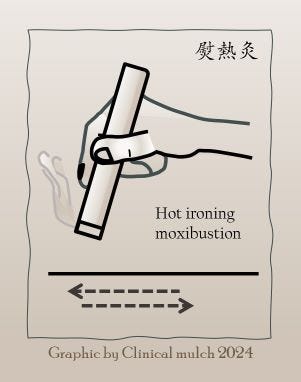

Also known as hot ironing moxibustion 熨熱灸

First described in 1957 by Tián Zhànyuán

Uses a circling or ironing motion, around or back and forth, 2-3 cm from skin for 20-30 min

There are two subtypes,

Flat circling moxibustion,平面回旋灸 píngmiàn huíxuán jiǔ

Spiraling moxibustion, 螺旋式施灸 luóxuán huíxuán jiǔ

Flat circling is moving the stick on a flat plane in a circular direction over the skin

Flat circling is better for larger areas, 20-30 minutes

Aim for localized flushing of skin

Spiraling moxibustion uses a spiral pattern maneuver descending toward point and then repeated

Spiraling is more used for smaller areas or acute conditions

Aim for a localized dark red reaction

Circling moxibustion is indicated for wind-cold-damp obstruction; skin diseases like shingles, neurodermatitis and pressure sores

Functions to invigorate blood flow, warm channels and networks, dispel cold, move stagnation

3 Sparrow pecking moxibustion

Once the moxa stick is lit, it is advanced toward the point (about 2 cm above skin) and then withdrawn repeatedly, like a sparrow pecking at food.

Usually treatment time is 2-5 minutes for each point

Rate of application is about 50 pecks over 3-5 minutes, or about 6-10 seconds each peck.

Stronger heat than other methods. Heat to tolerance but do not burn the skin.

Best to position point between fingers to gauge the heat

Indicated for acute conditions, joint pain, wind-cold-damp, abdominal pain, channel and network vessel strike, diarrhea, fetal malposition, pediatric diseases and fainting/reversal but has a wide range of indications and can be used to treat general illnesses

Functions to warm yáng, raise the sunken (阳起陷的), revive consciousness

Sparrow pecking origins

Sparrow pecking moxibustion’s history only dates back to the mid-20th century.

The term sparrow pecking first appears in lecture notes of Chéng Dànān in 1940 when it was used to describe a particular needle technique. The first mention of it in relation to moxibustion comes from Zhū Liǎn’s 新针灸学 Xīn Zhēnjiǔ Xué, [New Study of Acumoxa]. After that, references to the technique can be found with increasing frequency. Zhū Liǎn herself related an experience of twice developing gastroenteritis while traveling and using lit cigarettes to warm the treatment points, trying different methods (Huang et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2016) which may have been the prototype of mild vs sparrow-pecking techniques.

Sparrow-pecking can also be seen as a descendant of the pressing moxibustion techniques of the Míng and Qīng eras, except there is not barrier and the moxa stick is not pressed into the skin.

In relation to precursors of other methods, Wilcox (2005) mentions a technique for treating sores that is found in volume 64 of Jingyuè Quánshū (Complete Compendium of Zhāng Jingyuè) which sounds similar to the circling moxibustion. And, as mentioned earlier, Yè Tiānshì may well have been the progenitor of mild stick moxibustion.

Other considerations

The optimum time of treatment has been a subject of much debate and various studies have been undertaken to get a better idea. Some studies show that increased time from 5 to 10 or 15 minutes can have stronger effect. Other studies go up to 30 minutes or even an hour. (Zhao et al., 2016)

In his book Clinical Moxibustion Therapy, Li Guan-rong (Li, 2007) states that the optimum result is not a matter of time, but to treat until the patient’s lips turn red. Li attributes this to the presence of teardrop erythrocytes which indicate that the yáng qì of the moxa has induced the marrow to start pumping red cells out into peripheral circulation. Li only mentions one type of suspended moxibustion, which by his description would correspond to mild stick moxibustion.

Frequency and duration of treatment

Some studies show daily or every other day moxa has the best effect (Zhao et al., 2016).

As far as treatment course, it varies with the clinical situation; an interesting study was cited in Zhao (2016) that showed 1.5 months of suspended moxibustion to improve total cholesterol, but over 3 months to raise HDL cholesterol. A similar study showed 60 consecutive days of moxibustion could lower lipid levels.

Closing thoughts

Most of the sources cited here mention that suspended moxa stick moxibustion is useful for a wide variety of diseases. Huang et al, (2013) places the number at 269 different disease conditions treatable with stick moxa. However, the biggest drawback noted by almost all sources is that stick moxa is time-consuming and labor intensive. Li et al. (2016) discusses the possibility of some kind of automated solution, a “moxa-bot” of sorts. The time and labor factors combined with the optimum treatment frequency of daily or every other day sessions make the prospect of instructing the patient on self-treatment at home much more reasonable. Even very simple points like ST36, treated every day, can have profound effects.

That’s all I have for now. I plan to put up a few more posts discussing some areas of research specifically for stick moxa, and for moxibustion more generally. Thanks for reading.

Note: this publication is for information purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. Please seek the opinion of a health care professional for any specific medical issues you may have.

References

Huang, C., Liu, J.T., Liu, Y.M., & Zhao, B.X. (2015). Exploration on origin development and application of moxa stick moxibustion. China Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy, 30(12), 4218-4220.

Huang, Q.F., Liu, J., & Wu, H.G. (2013). Commentary on disease spectrum of moxa stick moxibustion based on acupuncture-moxibustion information databank. Shanghai Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, 2013(07).

Li, G,R. (2007). Clinical moxibustion therapy, 2nd edition. People’s Medical Publishing House.

Li, L.H., Wu, H.G., Wu, R.Z., Qi, L., Chen, P.S., Yu, S.G., Chang, X.R., Ma, X.P., Dong, H.S., Liu, H.R., & Li, J. (2016). Origin and Development of Bird Perking Moxibustion. World Chinese Medicine, 11(12) 2521-2524. Doi:10.3969/J.Issn.1673-7202.2016.12.003

Wilcox, L. (2005). A brief history of the moxa roll. Journal of Chinese Medicine 79, 48-52.

Yin, D.S., Zhao, Z.T., Cao, J., Chen, S.S., Bian, X.P., & Wang, M. (2020). Summary of three different ways of suspension moxibustion and their clinical application. Asia Pacific Traditional Medicine, 16(7), 199-201. DOI:10.11954/Ytctyy.202007064

Zhao, M., Li, H., Wu H.J., Zhang, J.B., Huang, Y., Bao, C.H., Dong, H.S., Wu, R.Z., Chen, P.S., & Li, J. (2016). How to improve the clinical efficacy of moxa stick suspension moxibustion. World Chinese Medicine, 11(12), 2539-2548. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1673-7202.2016.12.007