Over the last couple of posts, I have been reviewing some of the recent literature on the xuánfǔ, or Mysterious House, the tiny network of micro-structures that run through the entire body. Last week the subject was Chinese herbal medicine for opening xuánfǔ. This time around, I want to talk about acumoxa and other external therapies.

Lit Review

The literature search for “xuánfǔ acumoxa” [玄府针灸] came up with a small selection of papers, mostly disease-specific. My aim was to find some methodology for point selection in particular that would reflect a basic treatment strategy for opening the xuánfǔ. Here is a brief review of the papers I looked at.

Xiàng & Péng (2021) discussed deafness and tinnitus from the point of view of xuánfǔ theory, focusing especially on the shàoyáng channels. The shàoyáng channels are, of course, quite closely related to the ear, and in the discussion and case reports, there was no explanation of the points selected as they related to the xuánfǔ, only the more standard treatment principles [course channel qì, relieve deafness, benefit the ear, etc.]. The article mentioned the most common point for deafness as being TB5, which is a point that is often used in exterior patterns. Other shàoyáng points selected were TB1, TB2, TB3, TB4, TB6, TB7, TB8, TB9, TB10, TB16, TB19, and TB21, but these were all indicated for deafness, and were not specifically linked to opening the xuánfǔ.

Lǐ et al. (2021) looked specifically at migraine, with a case report involving acupuncture and herbal medicine. Migraines typically appear on one side of the head and frequently on the temporal aspect, so the article identifies them closely with shàoyáng channels. The root etiology and pathomechanisms they outline in the case of migraines is wind evil, hyperactive liver yang, inhibited shàoyáng channel qì, and blockage and obstruction of the brain xuánfǔ [风邪、肝阳上亢、少阳经气不利、脑之玄府闭塞不通]. The key treatment therefore is to course and free the shàoyáng channel, unblock and facilitate xuánfǔ, regulate and smooth out the channel qì [疏通少阳经脉、通利玄府、调畅经气]. The protocol they discussed was divided into attack and remission phases, though the point selection in each was much the same – only the technique differed.

Attack phase: TB20, GB8, GB20, TB5, GB34, and LR2 as first-priority points, with CV6 and ST36 added. On the affected side use āshì points, TB20, and GB8; GB20, TB5, CV6, GB34, ST36, LR2 are needled bilaterally. Electrical stimulation can be added as needed. Use even technique on GB8, CV6, and ST36; use draining technique on GB34 and LR2.

Remission phase: Same points as above but supplement St36 and CV6; use even technique on everything else.

The article highlights the combination of GB20, TB5, and GB34 and says these points “work together to course and discharge the Shàoyáng channels, free and facilitate the Xuánfǔ, unblock the network vessels and relieve pain [疏泄少阳、通利玄府,通络止痛].” Here, then, is a reference to points specifically unblocking xuánfǔ; they are all shàoyáng channel points, and two of them [GB20 and TB5] are directly associated with wind conditions.

Continuing the search, I came across a couple of papers related to women’s health which highlighted acupuncture in reference to xuánfǔ theory.

Xià et al. (2024) published a discussion of treating premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) on the basis of two theories: one regarding the “kidney/ tiānguǐ/ chōng-rèn/ bāogōng [uterus] reproductive axis” [“肾-天癸-冲任-胞宫生殖轴”] and the other being xuánfǔ theory. The connection between the two theories is that the xuánfǔ serve as the portal of regulation and control for the reproductive axis; it is the means of distribution for the qì-blood-fluids, which includes the tiānguǐ, or heavenly waters, which determines reproductive vibility. Tiānguǐ is produced from kidney essence, and replenished through the post-heaven essence, and depends on smooth flow of liver qì. Chōng and rèn are the channels that regulate the reproductive axis.

The main pathogenesis of POI is posited as kidney vacuity and insufficient kidney qì, mixed with spleen vacuity and liver depression, lack of tiānguǐ source, and stagnation of xuánfǔ, resulting in chōng-rèn vacuity and lack of nourishment to the bāogōng. Therefore, the treatment principles are supplementing kidney essence, strengthening the spleen and liver, regulating chōng-rèn, opening xuánfǔ and eliminating depression.

Most of the article focuses on the roles of the zàngfǔ, chōng, and rèn in treating POI. Interestingly, the primary etiology in xuánfǔ dysfunction mentioned concerns the role of the emotions. Xuánfǔ blockage is closely associated with liver depression and coursing liver qì is given an important role in opening xuánfǔ.

玄府为病,核心在于郁闭,故可根据行气、化痰、祛瘀的治则,经过随症加减,达到祛有形实邪以开无形之郁的目的。

Xuánfǔ dysfunction's core lies in depression block [郁闭], and therefore is treated on the basis of moving qì, transforming phlegm, dispelling stasis. Add and subtract following the disease process, in order to dispel tangible repletion evils by means of opening the depression of the intangible. - Xià et al. (2024)

To treat the emotions, the article recommends GV20, GB14, and HT7. To regulate fluid, use ST40 and SP9. To quicken blood and dispel stasis, needle UB17 and SP10.

Lù & Cài (2025) discuss the approach of Cài Shèngcháo [one of the paper’s co-authors] in treating perimenopausal insomnia (PI). Professor Cài was a student of moxibustion master Zhōu Méishēng. He sees vacuity in chōng and rèn along with xuánfǔ disturbance [玄府失司] as root etiologies of PI. Since the spirit, like other vital substances, travels through the xuánfǔ, disturbance in the opening and closing of xuánfǔ means that the spirit cannot freely enter, exit, ascend or descend, which results in insomnia. Age-related depletion of qì, blood, and essence, yīn-yáng disharmony, and liver depression qì stagnation are also factors leading to the disturbance of xuánfǔ.

Professor Cai created the “needling method to regulate ren, unblock the mysterious, and calm the spirit” [“调任通玄安神针法” “Tiàorèn tōng xuán ānshén zhēn fǎ”] based on his 50 years of clinical experience. The basic prescription is GV20, Sìshéncōng, Ānmián, CV7, CV12, and CV4. The first 3 points treat insomnia, the rest are rèn vessel points, which the article explains are chosen to regulate estrogen, increase 5-hydroxytryptamine, and inhibit norepinephrine. If there is essence and blood vacuity, then UB15, UB20, UB17, SP10, and SP6 are added to supplement blood and open the xuán to unblock the spirit mechanism. [补血开玄,以通神机]. If there is liver depression, unblock shàoyáng qì and add LI4 and LR3.

Are There Points to Open Xuánfǔ?

In each of these papers, though xuánfǔ theory is discussed, the point selection seems geared towards the presenting complaint and there is very little to go on with regard to choosing points specific to the principle of opening the xuánfǔ. To put it another way, in the last article, I reviewed several papers concerning Professor Wáng Míngjié’s approach of treating xuánfǔ by using a combination of acrid exterior-resolving wind-dispelling herbs with interior wind-extinguishing substances, most notably insect medicinals. The basic strategy was applied regardless of the presenting complaint; there were of course ingredients to address the other pathomechanisms of qì or yin vacuity, etc. But if you handed me a prescription with a combination of, say, qiānghuó [Radix Notopterygii], fángfēng [Radix Saposhnikoviae], quánxiē [Buthus Martensi], and dìlóng [Pheretima], I could recognize opening xuánfǔ as a treatment principle. In the papers reviewed above, I see no real common thread.

Methods to Open Xuánfǔ

Where a common thread does appear is in the discussion of methods and techniques to open xuánfǔ. The first paper I read that took this approach was Mǎ et al. (2024). The article discussed acumoxa treatment of facial palsy based on xuánfǔ and luòmài [network vessel] theories. Xuánfǔ are regarded here as a complement to the network vessel system. The xuánfǔ function like portals to the network vessels which are the transverse passageways that form a distribution system throughout the body. The luòmài are responsible for circulating yíng and wèi while the xuánfǔ regulate the inflow and outflow of blood and the transformation of yíng and wèi in the network vessels. In facial paralysis, the article says, the sequelae are attributed to poor circulation of qì and blood and blockage of xuánfǔ. Principle of treatment is open and unblock xuánfǔ, dispel stasis and free the luò [开通玄府、祛瘀通络]. Interestingly, the main thrust of the discussion is the treatment techniques, with the discussion of point selection entirely related to dispelling stasis and freeing the network vessels. No points were given to open the xuánfǔ; instead, two methods were discussed:

Cupping – using negative pressure to unblock the channels and open xuánfǔ

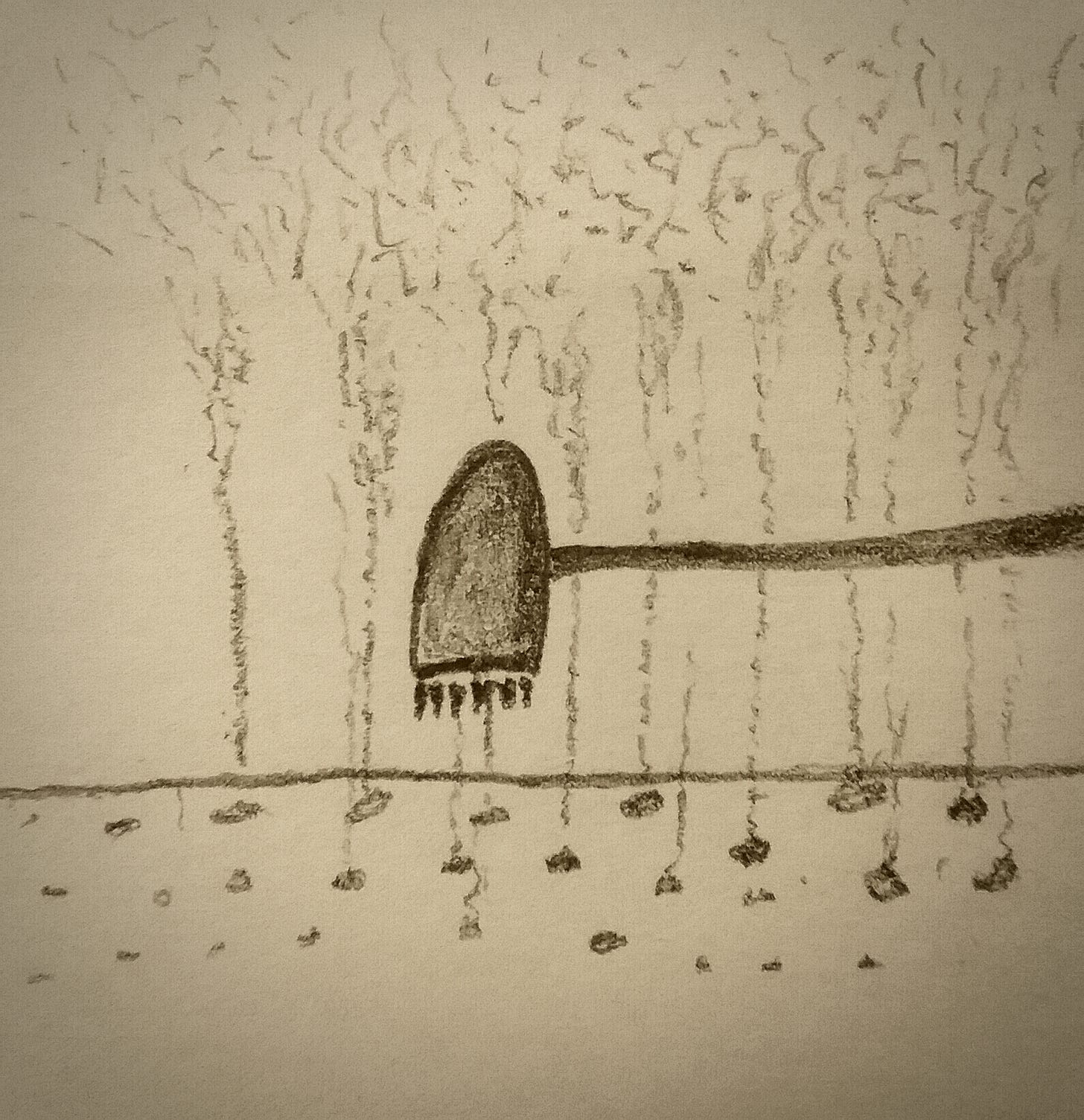

Plum blossom needle – stimulates superficial skin layer, opens xuánfǔ, vents pathogen preventing deeper penetration

Finally, I received a copy of Professor Wáng Míngjié’s 2018 book, Xuánfǔ Theory [玄府学说, Xuánfǔ xuéshuō]. In it, he discusses five external treatment methods to open the xuánfǔ:

Acupuncture – Specifically filiform needling and plum-blossom needling. According to the presenting pattern differentiation, the relevant acupuncture points, cutaneous regions, and areas with pathological changes on the surface are punctured in order to open the pores and unblock the xuánfǔ. Opening xuánfǔ locally, Professor Wáng says, will open the xuánfǔ of the viscera and all affected tissues throughout the body.

Bloodletting – Professor Wáng includes a quote from Zhāng Cóngzhèng [張從正, 1156-1228]: “letting blood and effusing sweat, though they have different names, in reality they are the same thing [出血之與發汗名雖異而實同].” Bloodletting opens the network vessels which are closely related to the xuánfǔ, and the removal of blood stasis can help open the xuánfǔ and restore the spirit mechanism.

Cupping – Fire cupping can warm the channels and dispel cold, and the negative pressure can help expel lodged evils such as cold and dampness. It is especially useful for cold and pain relief, but can also be used in cases of complicated diseases caused by vacuity, wind, phlegm, qì and blood stagnation, and so forth.

Moxibustion – Can be used to warm the channels but can also be applied in heat syndromes where it can release the stagnation of yáng qì in the body by unblocking the surface.

Steam-washing – Steam-washing [熏洗, xūnxǐ] is a method using steam from, or external application of, a medicinal decoction. Not only can the warmth from the steam open the xuánfǔ, but the medicinal properties of the decoction can enter through the skin and hair and spread through the xuánfǔ network systemically. The specific medicinals to be decocted and steamed depend on the presenting pattern differentiation.

One advantage to these methods, Professor Wáng points out, is their clinical utility, even in complicated and confusing cases. Though pattern differentiation is the fundamental principle in TCM, things are not always so clearly defined in clinic, and beginning with the principle of unblocking xuánfǔ can yield effective results even without a clear pattern diagnosis.

My thoughts

From this brief literature review on acumoxa treatment to open xuánfǔ, there seems to be little consensus in the way of point selection, and some agreement in the way of modality. The points presented in the articles I reviewed largely conformed to those which one might expect in cases that made no reference to xuánfǔ theory; the impression I get is that by treating the pattern, the xuánfǔ are opened. But why then involve principles of xuánfǔ at all?

As frequent mulch readers know, I am fascinated with [possibly obsessed by] point selection, and so I have a few thoughts of my own on the subject.

I think one of the reasons xuánfǔ theory piqued my interest is because it seems quite compatible with some of my other interests, most notably lurking pathogen theory, and the idea of venting the surface. In those cases, there was little in the way of discussion on acumoxa therapy that I was able to find, and so I wrote a paper about it for my doctoral program [which later turned out to be the impetus for starting to write Clinical mulch].

In the spirit – though not the specific recommendations – of Professor Wáng’s internal medicine approach, I would advance the following ideas:

Combine exterior-resolving points with points to quicken blood. This is an adaptation of the basic formulation strategy discussed in the previous post.

Use wind points [GB20, GB31, UB12, etc], and any points that regulate sweating [KD7, HT6, LI4, etc].

Use wood points, in the sense that the qì of wood is opening, rising, and effusing. Metal points, which are related to the surface, can also be considered. On that basis, jīng-well points in particular, being either wood or metal, and used to unblock channel stagnation, open orifices, and treat the viscera, would seem to be useful.

A couple of the articles reviewed discussed opening xuánfǔ through treating shàoyáng; it’s unclear whether that was specific to the conditions treated. However, many important wind and exterior-resolving points are found on shàoyáng channels, so I think it would be not off-base to focus on that channel in regard to general regulation of xuánfǔ. Shàoyáng is the pivot between interior and exterior, and the xuánfǔ are a series of portals that run from superficial to deep, responsible for the exit and entry, ascending and descending of vital substances.

The techniques to unblock the xuánfǔ that were discussed by Professor Wáng are likely to be more reliable than my scattered thoughts on the subject, of course. I would like to add a couple more for consideration, however.

Scatter needling [散鍼 C: sǎnzhēn, J: sanshin], a technique used frequently in Japan. In scatter needling, a single needle is used to lightly and quickly stimulate the skin surface over a fairly wide area. It is in some respects similar to plum-blossom needling but uses a filiform needle [or teishin] instead of the little hammer. I use it often and find it is very easy to calibrate the amount of stimulation produced. I basically never use plum-blossom and rarely use cupping – a personal preference – so for me sanshin is a preferred way to open the pores and unblock the xuánfǔ.

Heat-perception moxibustion [知热灸C: zhīrèjiǔ, J: chinetsukyuu], in which a cone of moxa about 1 cm in diameter is placed directly on the skin – usually the bottom of the cone is moistened with water to help it adhere – and lit, allowing it to burn down until the patient indicates they feel the heat [or until it is burned about 2/3 down, whichever comes first]. This technique is specifically used in Japan to treat inflamed tissue by using the heat to open the skin surface and vent it outwards (Hayden, 1999).

Conclusion

I got a lot out of researching this series of posts. It’s what keeps me going, really: the vast scope of ideas in Chinese medicine and the need for lifelong study. I’ve had 30 years in practice as of this year, and the learning never ends. I am having a great time working through Professor Wáng’s book, connecting the material to what I’ve already learned, and investigating the ideas that are unfamiliar to me. I hope you too have gained some benefit from these posts.

That’s all for now, thanks for reading.

Note: this publication is for information purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. Please seek the opinion of a health care professional for any specific medical issues you may have.

References

Hayden, R. (1999). Thoughts on using chinetsukyu in meridian therapy. North American Journal of Oriental Medicine (NAJOM), 6(17), 18-19.

Lǐ, X., Zhǎn, L., Tán, S., Xing, B., & Liú, W. (2021). The application of xuanfu theory in migraine prevention and treatment. Shaanxi Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 42(12), 1748-1751. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-7369.2021.12.025

Lù, S., & Cài, S. (2025). Professor Cai Shengchao's acupuncture treatment for perimenopausal insomnia based on the “xuanfu” theory. Acta Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology, 53(1), 62-65. DOI:10.19664/j.cnki.1002-2392.250011

Mǎ, F., Xu, X., & Wáng, H. (2024). Discussion on acupuncture and moxibustion treatment of sequelae of facial palsy based on the "xuanfu⁃luomai" theory. Shanghai Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 58(9), 13-16. DOI:10.16305/j.1007-1334.2024.2311146

Wáng, M., & Luó, Z. (2018). 玄府学说 [Xuánfǔ xuéshuō]. People's Medical Publishing House.

Xià, X., Liáng, Y., Dǒng, L., & Yáo, X. (2024). Discussion on acupuncture treatment of premature ovarian insufficiency from "kidney-tiangui-chong-ren-uterus" reproductive axis and "xuanfu theory". Academic Journal of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 38(4), 87-91. DOI:10.16306/j.1008⁃861x.2024.04.012

Xiàng, H., & Péng, B. (2021). From the theory of xuanfu to the diagnosis and treatment of deafness by acupoint selection in the distal part of the three-jiao meridian of the hand shao yang. Asia-Pacific Traditional Medicine, 17(12), 135-137. DOI:10.11954/yctyy.202112036