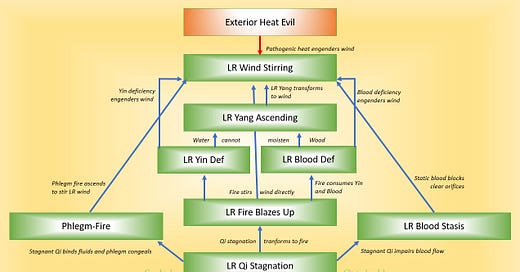

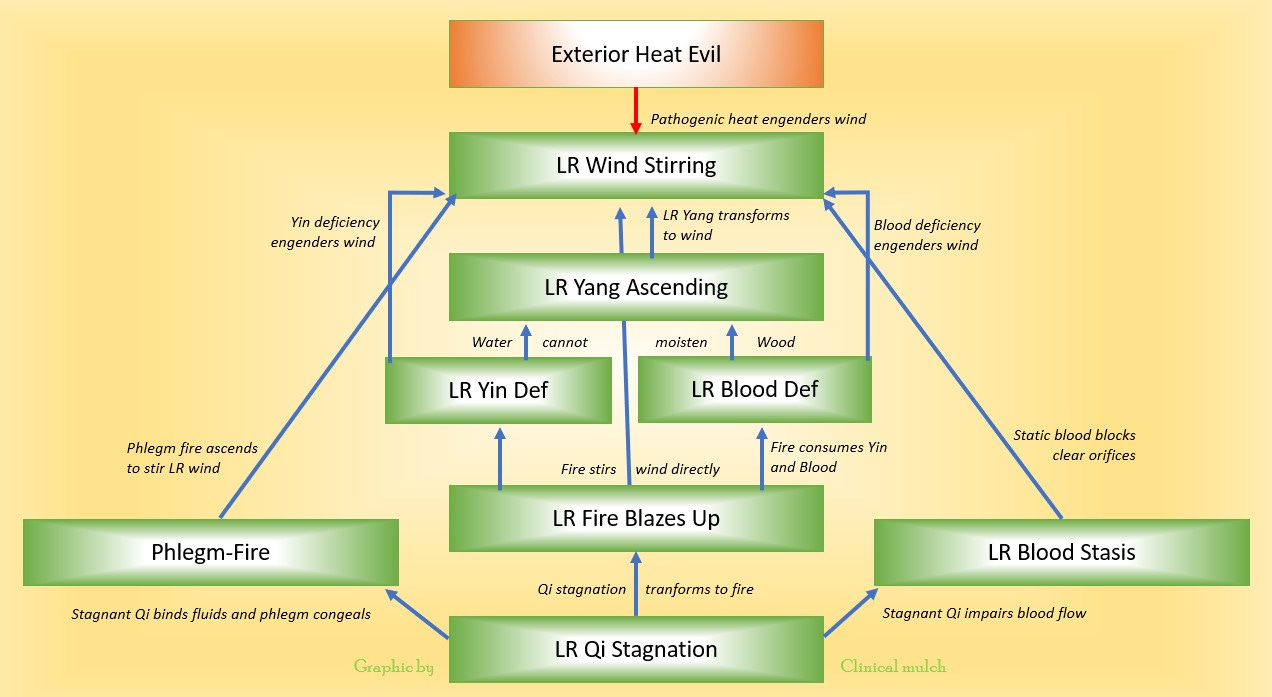

I've been working on some lecture materials this week. Here is a chart I came up with primarily to show the pathogenesis of liver wind. The lecture is for first year of an entry-level professional program in acupuncture and Chinese medicine. This is the iterated version. I abstracted the original chart from Yán & Lĭ (2007) and adapted it to better fit the pattern flow in Maciocia (2015). I posted it on Facebook and after a conversation with some colleagues and former students, I figured a way to add some pathomechanisms — hopefully without making the thing too incomprehensible.

The major zàng-fǔ and pathogen patterns are in the boxes, with arrows showing the development of subsequent pathology. In italics between these structure are brief descriptions of the pathomechanism.

Some thoughts on the chart:

Etiological factors preceding the bottom-level patterns are not shown; for example, the role of the spleen in transforming fluids is implied but not explicit in the development of phlegm, and the role of the kidney in yīn deficiency has not been shown.

Although there is considerable overlap in symptom sets for liver yáng and liver wind (headache and dizziness being chief among them), it is important to understand that the pathomechanism for liver yáng ascending comes from yīn-blood insufficiency, or water unable to moisten wood. Liver wind typically involves involuntary movement (twitching, spasm) or lack of motion control (paralysis) which is not limited to the upper body. Liver wind also, as shown in the chart, has multiple routes of pathogenesis.

According to Yán & Lĭ (2007), although the pathomechanism for hyperactive liver yáng ascending was described in the Sù Wèn, the pattern was not defined as such until Yè Tiānshì wrote about it in the Qīng era.

Phlegm stirring wind is not listed as a discrete pattern in Maciocia, though phlegm often ends up in the discussion anyway. Phlegm-fire can also contribute to the development of liver yīn deficiency/vacuity and thus liver yáng ascending, but the mechanism is very similar to qi stagnation and liver fire. For the sake of simplicity, I decided to emphasize the pathway leading to the development of wind directly.

Liver fire can lead to liver wind through dessication of liver blood and yīn leading to ascending yáng, or, if the fire is intense enough, through direct stirring of wind. I attempted to show this in two dimensions by an arrow slightly angled in the background and a descriptive phrase but the attempt may not have been successful.

Blood stasis itself is not a direct pathway listed in either Maciocia or Yán & Lĭ; however, I do believe blood stasis in the network vessels to be a pathomechanism leading to liver wind - I see this frequently in clinic - but for reference I had to go to Wáng Qīngrèn.

The entirety of warm disease theory is subsumed under "Exterior Heat Evil - Pathogenic heat engenders wind". For purposes of the lecture (which is in a course on zàng-fǔ patterns as opposed to a one on exogenous febrile diseases), we're not considering the development of interior wind within the four levels, and if we did the chart would become insanely complicated.

Charts such as this one can be very helpful in understanding pathogenesis but one needs to keep in mind their limitations. For one, flow charts impose a linear structure onto what might be better described as a circular or spiraling process. It is easy to look at the chart as a map, as in "last week we were in liver qi stagnation, but this week we are passing through liver fire and we'll be in liver yīn deficiency by the preekend." In truth, the relationships pictured by the arrows are not one-way so much as they are mutually engendering; thus the necessity of formulas such as Zī Shuǐ Qīng Gān Yǐn (Water-Enriching Liver-Clearing Beverage).

This type of decision-tree presentation is one of the reasons why Ogawa (1996) considered TCM to be more like Western medicine than Eastern. I heard this directly from Ogawa sensei around the time of his article publication, and the thought stuck with me for a long time. However, after almost three decades of teaching TCM as well as practicing (in varying degrees) both Japanese meridian therapy and TCM, I'm not so convinced. Perhaps the issue is our own thought limitations, in taking the map — however useful in certain contexts — as the territory. Certainly investigating the rich soil from which our practices sprout, in the form of re-discovering and plumbing the depths of the textual wellsprings of the medicine has opened up a vast field of possibilities for better comprehending this path we have undertaken.

Note: this newsletter is for information purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. Please seek the opinion of a health care professional for any specific medical issues you may have.

References

Maciocia, G. (2015). Foundations of Chinese medicine: A comprehensive text (3rd edition). Elsevier Health Sciences (US).

Ogawa, T. (1996). Comparison of traditional Chinese medicine and meridian therapy. North American Journal of Oriental Medicine, 3(6), 6-11.

Yán, S.L. & Lĭ , Z.H. (2007). Pathomechanisms of the liver (Sabine Wilms, Trans.). Paradigm Publications.